On the big screen, archives are generally mysterious places. Archives both hide and reveal secrets that move the plot along. But one of the biggest mysteries in fictional archives is how all that stuff got into the archives in the first place. Somehow old documents have magically and conveniently gravitated to the archives. Mythical archives are just there and they have everything.

“If an item does not appear in our records, it does not exist,” says the steely-eyed doyen of the Jedi archives in Star Wars: Attack of the Clones. No real archivist will ever say this. Read this post to find out why.

In real life, modern archives are no accident even if some of the archival records housed in them may have survived by chance. Archival institutions are methodically shaped by the decisions of archivists working together with other professionals. They are an intriguing result of both chance and choice, and they don’t keep everything, both by chance and by choice.

So far in this blog series we’ve discussed fundamental archival tasks including organizing and describing collections. In this post we’ll touch on something even more basic: the way archivists build up the collections of their institutions.

We’ll outline several basic truths about collecting records that surprise many people. For instance,

- There’s more to an archival record than its age.

- Archives don’t keep everything.

- “Everything” doesn’t exist to keep.

The process of obtaining records for an archival institution is called acquisition. The process of deciding what records should be acquired is called appraisal. These interrelated tasks are at the heart of the archival profession.

Of all the responsibilities of archivists, these are weightiest: the judgement of archivists will help determine how the future views the past. As we’ll see, this makes archivists uneasy – and that’s a good thing.

In The Fellowship of the Ring, Gandalf finds exactly what he needs by rifling through random stacks of paper. Gondor’s archives were not in Tolkien’s books. Perhaps this is because as an experienced researcher Tolkien knew what real archives are like!

Where archival records come from: Life before the archives

Archivists themselves don’t create the records they collect in archives. In fact, archival records do not start out being “archival.” They are created in as many places and circumstances as people are found.

Let’s recall what a record is. As we live our daily private, professional, and organizational lives, we tend to document our thoughts, beliefs, agreements, and observations by expressing them in some kind of fixed format. We create records so we can refer to them. Documents of all types help us to remember, to share, to compare, to analyse and to synthesize information.

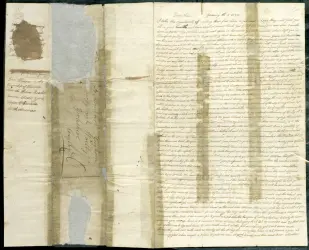

This letter from Peel to Yorkshire in England made two trips across the Atlantic and was passed down through generations of family members. It survived because it mattered to a few people. Now it matters to many more. (Hannah Young letter, Region of Peel Archives)

A record can be as ephemeral as a shopping list and as formal as a set of board minutes. It isn’t necessarily textual; it can be a voice memo, a video file, a map, or a photograph. Records are often called primary sources of information because they’re intimately tied to particular people doing particular things at particular times and places. Records reveal events as they unfold.

What happens to records over time? Because records are created for specific purposes, they don’t always survive beyond their initial usefulness. In fact it’s fair to say that most records are disposed of by the people who created them, if not by the people who come after them. As well, like any other physical objects, records can be destroyed by neglect or accidents.

Some records, however, do survive for a host of reasons: a writer might save drafts of a novel to capture her abandoned ideas; a family may cherish old photographs of a homestead to remember their roots; a business may save tax records to comply with the law. Or records might survive simply because they get overlooked in a cupboard or abandoned building.

But no records automatically come into archives. For this to happen requires decisions and planning both outside and inside the archives.

This portrait of an unidentified young woman survived because it was one of several thousand glass negatives recovered from the attic of an abandoned shop (and because the shop’s new owners alerted the archives). Unidentified photographs are generally low in specific informational value. However, this photograph is archivally valuable because of its unusual subject matter and because it’s part of a substantial body of records related to a local photography business. (Brampton Studio Collection, Region of Peel Archives)

How records reach the archives

Archivists themselves have varying levels of control over whether records ever reach their doors. (They have much more control over what gets through the doors and into the collection, as we’ll see).

To see why, it’s useful to think of records coming to the attention of archivists from two main directions.

Some archives acquire records through the organization the archives serves. For example, government archives collect records produced by the government itself; business archives collect records that document the workings of that business.

This is not an archives. It’s the records centre of one of our constituent municipalities. Records go here when they’re no longer in current use but still need to be retained for possible reference. Only some of these records will eventually come to the archives. Records managers oversee the efficient and lawful maintenance of records before they come to the archives. (Records don’t maintain themselves and can easily become lost, distorted, or orphaned.)

In these cases, archivists can analyse the types of records their organization produces and recommend what should eventually come to the archives. By working with records managers and others, they can flag likely candidates for the archives before records are even created – this allows archives to expect and plan for them. An organization’s archivists can also vet records before they’re otherwise disposed of to make sure nothing of archival value is lost. (How long records are kept is often dictated by legislation like tax, privacy, safety, or labour laws, and by whether the record is active, that is, still used for current business. Active records aren’t sent to the archives because they need to be on hand for frequent consultation.)

People are often surprised to learn that typically only about five percent of most organizational records will be preserved permanently in the organization’s archives (we’ll see why in a moment). We call the acquisition of such records a transfer because the ownership of the records isn’t changing; they are simply coming into the care of the archives for permanent preservation and research access.

In contrast, records can also come to an archives from the wide world outside the archival institution’s organization. Many archives collect records that centre on topics or themes, like a geographical locale, a social or cultural community, or a research subject. Unless the archives acquires these records, it doesn’t own them. The archivist therefore has limited say in what comes to the archives: not only are people entitled to keep records they own, but owners may not

Government records weren’t always kept to the standards we now try to maintain. We inherited records from Chinguacousy Town Hall, which was affected by a flood in the 1950s. You can see from this picture why some of those records are missing from our collection. (Brampton Guardian fonds, Region of Peel Archives)

know archives exist, let alone that archives might be interested in receiving their records.

Archivists do sometimes tactfully solicit donations of records when they learn about significant documents in private hands. We spread the word that archives represent the best chance for a person or group’s records to be preserved indefinitely and appreciated widely. Archives also occasionally purchase records that come up for sale. But beyond these measures, we can only consider what’s available for consideration.

How records get into the archives

We’ve just seen a few reasons why the records offered to archives are already a remnant of what people produce: people throw out or lose records; and archivists have limited control over what records are offered to the archives.

Does this mean that archivists accept all records that do come their way, provided those records are “old”? We’ve already hinted the answer is no when we said that only a small percentage of organizational archives are preserved. Now we’ll see why.

For one thing, even given the attrition factors mentioned above, people and organizations make and accumulate so many records that it wouldn’t be feasible to save them all permanently. Over the centuries the volume of documentation people create continues to skyrocket because of technological developments, from cheap paper and easy printing and copying, to proliferating digital options, storage, and replication.

We also need to remember that permanently preserving records is a big investment of space, energy, and time: stored archival records are not tucked passively away but must be documented and maintained, digital records included. (To learn more about how archivists take care of records, check out our posts under Archives FAQS and Facts.) In this sense, more important records will compete for time and attention with less important records.

Lastly, most archivists think that even if it were possible, it wouldn’t be wise to try to save every record ever produced (even digital ones that take up relatively little space). Some documents are near duplicates, some contain little information, and others summarize or include the results of others. Less important documents clutter the field of inquiry, making the more important ones harder to locate physically and conceptually.

Easy computerized printing led to an explosion of paper in organizations (which continue to produce vast amounts of paper records along with innumerable digital records). While technically every printout reveals something about work processes, it’s neither necessary nor desirable to save them all.

Appraisal: An act of balance

Over time archivists have devised ways to winnow down and control the deluge of records to those worth permanently saving. Archival records are a further small subset of all the records that survive. The act of making judgements about what records are archivally valuable and worth saving permanently is called archival appraisal (to distinguish it from monetary appraisal).

We’ve referred to some records as more important and worthy of preserving. If it sounds like this involves a value judgement, that’s because it does. There are a few important things to remember about appraisal:

- Archivists don’t appraise in a vacuum. We use collection policies and appraisal guidelines as a check list for archival value. These criteria help archivists to distance themselves from their own unique whims and prejudices.

- There is no exact formula for appraisal. Using criteria won’t give us an automatic answer of “keep” or “don’t keep.” Appraisal involves weighing multiple factors in the light of context and research. This informed judgement involves training, skill, discernment, a wide general knowledge, some subject expertise, and a firm grasp of the archives’ current holdings.

- Appraisal is never over. Archivists appraise records before they acquire them. Then they continue to appraise them as they process those records, when they may cull additional items. The shape of the institution’s entire holdings is also kept in mind, so that archivists can try to address underrepresented topics or people in their collections.

- Context is everything. The archival value of individual items is very dependent on their relationships with records surrounding them. The position of an item within a group of other records can determine whether that item is kept or culled. (For more on the crucial importance of the relationship between records, see our post How do archivists organize records?)

- Archivists show their work. We document the appraisal process and what we keep and reject. We try to clarify our own thinking process and what changes we’ve made to a body of records so that the original state and function of those records is clear to researchers.

The archivist here is accessioning a small transfer of government records that have arrived from a government records centre. Every file must be accounted for. After records are accepted into the archives they receive an accession record, including a control number and a brief description that will draw on the appraisal review. This record will serve as a snapshot of the set of records until they can be processed.

The appraisal process goes something like this.

Some archives, like the Region of Peel Archives at PAMA, collect both their own organization’s records (in this case the records of four current governments and many historical municipalities) and records from external agents like individuals, organizations, and businesses.

When records are offered to the archives, the archivist gathers information about them. This information comes both from the contents of the records themselves, from the donor or creator of the records, or from additional research. The archivist wants to learn (if possible) who created the records, why, and when; this information will factor into the archivist’s appraisal report and later into the description of those records. Then the archivist considers things like these (among others):

Connection to the archives’ collection mandate. No archives collects records on every topic. We all specialize. If we didn’t, our collections would be unfocussed and researchers would have to search hundreds of institutions for records on their topic. Our specializations are carefully outlined in collections policies. If something is offered to us that doesn’t fit our mandate, we’ll often help donors find an institution with a better fit.

| The Region of Peel Archives collections mandate

The Region of Peel Archives collects, preserves, and provides access to records of archival value, regardless of media or format, that provide evidence of the decisions, policies, and activities of the Region of Peel, the City of Mississauga, the City of Brampton, and the Town of Caledon (plus all municipal predecessors). The Archives also acquires, preserves, and provides access to non-government records, regardless of media and format, that make a significant contribution to an understanding of the history and development of the Peel area, its natural and built environment, and the people who have lived in, worked in, or had an impact on Peel. |

Information and evidential value. Records worth keeping forever need to tell us something. People often correctly think of archival records as telling us about history: about the people, places, and events that have made us who we are.

This 1911 fire insurance map of Brampton has informational, evidential, artefactual, and aesthetic value. It shows us how the maker helped to insure buildings, the footprints of those structures, the way revisions to the map were made (by pasted patches) and the way watercolour was applied by hand. Region of Peel Archives)

It’s important to remember that records also represent evidence and therefore tools for ensuring consistency and accountability: properly maintained records function as proof of what happened, when, and why. For example, government correspondence or council minutes can show who made decisions that affect many lives. Evidence in records allows employees, citizens, and other researchers to check for themselves whether policies and procedures have been followed and at what cost. (Of course the same records can function both as evidence and as historical information: bylaws, for example, show what laws were and perhaps still are in force, but they also tells us about the concerns of the society they come from.)

Other types of value. The archivist also considers other types of value like artefactual value (the qualities items have because of their design or physical makeup) or aesthetic value (the artistic or appealing qualities of the items).

Rarity. Because there’s a premium on archival storage space, we’re more likely to keep records that are unique or rare – that is, records that are one of the few sources of the information they contain. Many archives only keep published resources if they shed light on a larger body of records since the information they contain may be widely available elsewhere.

Activity status. It’s not a good idea to store records that are still being used (and perhaps changed) for daily practical business in the archives. Archives aren’t just about storage but about highly controlled long-term preservation for reference access: we collect retired but still informative records with enduring value.

Reliability and authenticity. Since archival records are used for decision making and for developing our communal self-understanding, it’s very important that they are what they seem or claim to be. Archivists strive to verify the sources of records and to make sure that records are not altered or tampered with on their journey to and within the archives. Digital records present special challenges here – they can be altered and duplicated more easily and anonymously. Technical expertise is needed even to define what makes an electronic record authentic.

Informational density. Records rich in information are more valuable than those containing little; when information is thinly dispersed over a large volume of records, some of those records may be candidates for careful selection or sampling: these are techniques archivists use to capture what is most revealing about large volumes of similar records (see the inset on receipts below).

Some records are in such poor condition when the archives receives them that unless they’re extremely rare and informative it isn’t worth trying to save them (they could also endanger other records, as in the case of the mouldy records on the right).

Completeness. Archivists are often reluctant to split a group of interrelated records because this spoils the revealing connections between them. If donors offer a part of a body of records, we may try to convince them of the greater value of the whole. In general, the more complete a run of detailed records is, the more valuable it is (a whole diary is more valuable than a page ripped out it; a decade’s worth of diaries can be even more valuable than a single diary).

Physical condition. The condition of records affects how we can read, use, and store them. One factor in acquisition may be the associated monetary cost of stabilizing or conserving items. Given other factors noted above, it may not be worth doing so; at the very least, the dollar cost of doing so will be carefully considered.

To appraise the contents of these floppy disks you need to open the files. The only clue to their contents might be written on the disks or in documentation that arrived with them. What if it isn’t?

Again, digital records present a special problem; if they’re created with long-term preservation in mind they stand a better chance of being accessible. But when archivists receive electronic records on old media or in unknown file formats, content can’t even be appraised until we figure out how to access the old files. If there’s no context to the records, it’s difficult to know whether it’s worth trying to open files at all. Meanwhile every month and year the digital records await appraisal and processing they become more obsolete and more difficult to access. For digital records, then, technical requirements and challenges are part of the appraisal process.

Conditions of access. Archives are acquired to be used, so archivists need to consider restrictions that might affect access. Some limited restrictions are normal and dictated by privacy law or the wishes of donors: for example, sensitive or private information may not be open to researchers until a reasonable period has passed. If a donor requests complicated or problematic restrictions (such closing his records to people he doesn’t like) acquisition may not be possible. Archivists also need to be aware of the legal status of records, such as how copyright applies to them.

| The case of receipts

Receipts are a record type that archivists often don’t keep – but it depends. Context is everything, as these examples show. Receipt from chain pharmacy, 2016. With no context this receipt has no archival value. There are millions of such receipts; it’s not rare and neither is the business it comes from. It tells us only that some unknown person bought some items on a certain day. But what if the receipt was enclosed in a letter from a refugee about her first purchase in Canada? Building materials receipt from a local business, 1883. This older receipt reveals more information than modern receipts do – it gives us an idea of building materials (and even methods) of its time. It also mentions the name of the purchaser and the address of a unique local business, now long gone. Receipts like this can also have aesthetic value because of sometimes elaborate typesetting and letterhead illustrations. Drawer of receipts from local business, 1940s. It would be a challenge for the archives to keep every one of these receipts from a mid-century garage and repair business; also, each receipt contains limited information. One option is to take representative samples to show the change in the business over time. |

Acquisition, the future, and you

We hope that this post gives our readers an idea of how archivists get archives and why we keep what we keep.

Archivists are always considering and reconsidering their role in shaping the historical and evidential record. Here are a few of areas of lively discussion that we haven’t even touched on in this post (but will in a future post). They include asking how

- our archival institutions may currently reflect a historical world view that needs updating or broadening

- people and groups come to be absent from the archival record

- appraisal processes need to evolve with the demands of digital data

- we can deal most compassionately with donors who are grieving loss and change

For now, we’ll leave you with the following thoughts. The appraisal criteria above may sound a bit daunting. People sometimes are alarmed when they hear that archivists don’t accept some old things and that they might even dispose of them. (Note that this is never done without a donor’s permission).

Donating to an archives involves having a conversation and signing a deed of gift to clarify context and donor requests, and to pass ownership of records to the archives. Owning the records allows the archives to invest in their care and to keep them safe and available for research.

If you’re wondering about the sorts of things we don’t keep, here’s a list. But keep in mind that there are always exceptions to anything on this list. Context is everything.

In general we find that people underestimate the archival value of their own unique records. If you have documents you think might have archival value (which, again, is not the same thing as monetary value) speak to an archivist. We’re always happy to advise. When in doubt, don’t throw it out. Without you there would be no archives.

Posted by Samantha Thompson, archivist

All photographs by the Region of Peel Archives except municipal records centre (courtesy of the City of Mississauga) and box of floppy disks.

Another fantastic post. Thanks for this brilliant summary. Your descriptions of archivists’ work are really second to none.

LikeLike

Thank you, your encouragement is much appreciated.

LikeLike

Absolutely wonderful blog. Thanks for writing it.

LikeLike

Thank you for your feedback, much appreciated!

LikeLike

I am so happy to have found this blog. I enjoy reading the posts very much and have even cited one of the posts for a class blog recently. I seem to find words in these articles that make me stop and appreciate archives and records management more than I already do.

My pick today is “the judgement of archivists will help determine how the future views the past”.

No pressure.

Cheers

LikeLike

Thank you for your lovely comments Claude – it’s so kind of you to take the time to tell us how we’re doing. Like you, we’re more in awe of our responsibilities every day. Best wishes for your own archival pursuits.

LikeLike

What a lovely surprise to see Jocasta Nu – played by my dear friend Alethea McGrath – pop up in my Inbox. Sadly, Alethea died several years ago but she knew I was an Archivist and we chatted about her Star Wars role and my work many times.

LikeLike

Wow, how interesting! Life makes all kinds of interesting connections. Thanks for dropping by to tell us about this one! All the very best Kathryn.

LikeLike

Great article thanks. I have actually done some data migration of old floppy discs to an EDRMS using an external drive. These records are often at risk – neglected and overlooked for paper records. Unless they are migrated we risk losing electronic records to the digital “black hole”…

LikeLike

Thank you for emphasizing an important point based on your own experience. Digital preservation and the digital black hole are such complex and frankly troubling issues that they deserve their own article! Luckily there are people like you working away to mitigate some of the loss.

LikeLike

Maybe I can be wrong but I stil think that the best plataform is the old and good paper. We can read (“access”) a paper wrote thousands of years ago and will be ablet to do it again in thousands years ahead although it is kept preserved.

LikeLike

You are not wrong! Very little in the way of special equipment is need to access paper records (which can last a lot longer than people think), or even microfilm (all the latter needs is a light source and a magnifying glass). But accessing digital records requires a whole infrastructure of incredibly complex software and hardware, plus of course a power source.

LikeLike

Pingback: The Archivist’s first month PART 2: Insights and Impressions from the St Mark’s Photographic Collection – A STUDY IN SPECIALISM: cataloguing and conserving the archives of St Mark's Hospital·

Pingback: Que conserve (ou non) un archiviste? | Convergence·

Pingback: Archives and modern mythology: The use of archival records in comic books | Archives @ PAMA·

Pingback: An archivist’s night at the movies part three: Holiday edition | Archives @ PAMA·

Pingback: Family history, records, and Carmen’s journey of self-discovery – Genealogy in Popular Culture·

Pingback: Archival Practice – Curating the Clinical·

Pingback: Archives, Archivists, and Dealing With the Trump Presidency – My Life As Prose·

Pingback: Archives, Archivists, and Dealing With the Trump Presidency·

Pingback: Archives, Archivists, and Dealing With the Trump Presidency - Zox News·

Pingback: Popular culture and the duties of archivists – Wading Through The Cultural Stacks·

Pingback: Is Jocasta Nu in “Star Wars” an archivist or…a librarian? – Wading Through the Cultural Stacks·

Pingback: Archivists are not librarians: Understanding the differences – Wading Through the Cultural Stacks·